The Jet Set

Nature’s black magic

The word jet used to conjure up images of clouds flying by below and a gut full of excitement, but not so these days. These days the jet I’m thinking about is black and shiny and used in jewellery. I didn’t know anything about it and wonder whether I can tell you anything you didn’t already know on the subject; I hope so!

Jet isn’t a gem, right off the bat. It’s called a mineraloid which means that it’s actually the wood of the Monkey Puzzle tree (Araucaria araucana), millions of years old, that has been under intense pressure which causes it to change from wood to stone. There are two kinds of jet – ‘hard’ and ‘soft’. Hard jet is the result of carbon compression in salt water and soft jet is the result of carbon compression in fresh water, but in fact they’re both incredibly hard, but ‘soft’ jet tends to fracture in extreme temperature changes, apparently.

Because it’s millions of years old it stands to reason that jet is one of the oldest known ‘gems’ to be used in jewellery, being traced back as far as the Neolithic period (10,000 years BC) from which time a string of beads has been found. Since then not many examples of jet have been found which would indicate that it rather fell out of favour. Then in Roman times it was a hot item again mostly because Britain was occupied by the Romans who discovered the now very famous Whitby Jet in Yorkshire, which they used for their own decoration and exported to other parts of their Empire. The Romans believed jet had magical properties and mostly used it for amulets and pendants, and even today on the gemstone properties websites jet is credited with being quite a magical ‘gem’. Whitby jet is still considered to be the best quality jet in the world, with Spanish jet coming in a close second.

After the Romans, jet once again lost favour – why, I wonder – and it really wasn’t until the Victorian era that it made its huge comeback. Queen Victoria wore a good deal of jet mourning jewellery and naturally it caught on again in the fashion world. There are some absolutly astonishing pieces of Victorian carved jet jewellery; it takes a fantastic shine and can easily be cut, faceted and carved. In the 20s the Flappers loved jet beads because it’s very light weight so their long strings of beads were fun and easy to wear, and brooches and earrings could be large and elaborate without tugging on earlobes or coat lapels.

But jet can easily be substituted with other materials like glass, ebonit (vulcanised rubber) and anthracite (hard coal); the only non invasive test I know of to tell the real article from the fake is that glass is cold and jet is not, but it’s so easily mimicked that it’s really down to trusting your dealer to only sell you the real thing. However, if you really, really need to know whether it’s real or not, you can heat the tip of a pin and burn it into your piece of jet (pick an unobtrusive place, obviously!) and it will smell like burning coal. If it’s plastic it will smell acidic, and if it’s ebonite it’ll smell like burning rubber.

While not the most sought after gem these days, there are one or two contemporaries of ours that work with Whitby jet and they do make wonderful pieces. Jacqueline Cullen comes to mind immediately, and she combines Whitby jet with black diamonds and yellow gold to great affect; jewellery doesn’t get much more organic than that!

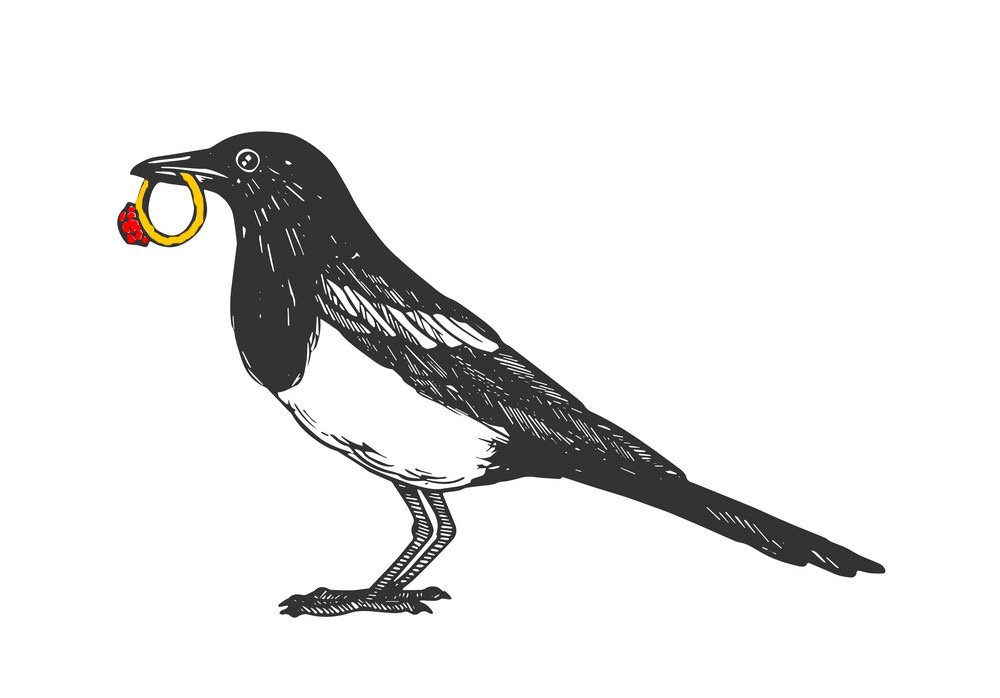

Of course the most obvious factoid about jet is that the expression ‘jet black’ means extremely black, but this wouldn’t apply to the ‘jet black’ feathers on a magpie because they’re actually shot through with astonishing colours, but I suppose from a distance….